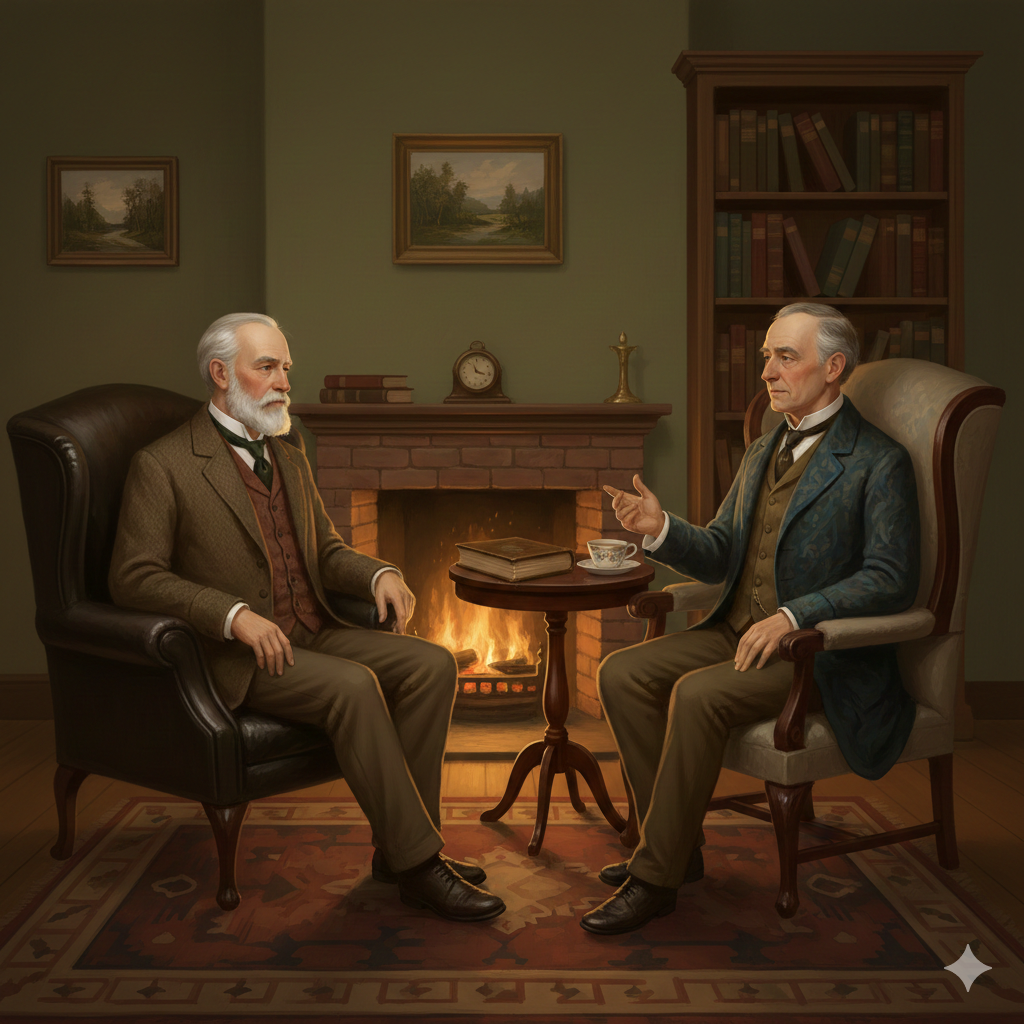

Christmas and the Spirit of Democracy was written, in 1908, by Samuel McChord Crothers (audio here [#23]/E-text here). It is a reflection and discussion by a fireside with Ebeneezer Scrooge–many years after his visits by the Ghosts and his momentous transformation, detailed by Charles Dickens in A Christmas Carol–and a colleague (friend).

Brief Overview

Samuel McChord Crothers’ “Christmas and the Spirit of Democracy” is a reflective and quietly provocative essay that begins not with politics, but with a familiar Christmas scene: a man by the fire, rereading Dickens and pondering what the season truly means. From this warm, literary starting point, Crothers gently leads the reader into a deeper question—why Christmas has such enduring power to soften hearts, break down barriers, and momentarily unite people who otherwise live divided lives.

Rather than treating democracy as a system of government, Crothers explores it as a spirit—a way of seeing others as equals, worthy of dignity, generosity, and fellowship. He suggests that Christmas, at its best, awakens this spirit by reminding us that human worth does not depend on status, wealth, or success, but on shared humanity. Along the way, he draws on literature, social observation, and moral insight, offering both gentle humor and pointed critique.

The essay is neither sentimental nor cynical. Instead, it challenges the reader to consider whether the goodwill of Christmas is merely seasonal emotion—or a glimpse of how society ought to function all year long. Thoughtful, accessible, and surprisingly relevant for a piece written in 1908, this essay rewards readers who enjoy ideas, moral reflection, and the way faith, culture, and public life shape one another.

The Central Question

Why does the spirit we associate with Christmas so naturally express the deepest moral meaning of democracy—and why is that spirit so hard to sustain the rest of the year?

Answering the Central Question

Q1. What is the spirit (moral meaning) of democracy (not the political system)?

The spirit of democracy, as Crothers understands it, is the moral habit of recognizing the equal worth and dignity of every person. It is not about power, rights, or procedures, but about how people regard one another. This spirit expresses itself in sympathy, fairness, humility, and a willingness to meet others as fellow human beings rather than as social categories. Democratic spirit resists arrogance and indifference, refusing to measure people by wealth, education, status, or usefulness. At its core, it affirms that every life matters and that society functions best when individuals willingly practice mutual respect and goodwill. Democracy, in this sense, depends not on laws alone but on character—on citizens who choose generosity over superiority and fellowship over exclusion. Another way to put it is, Crothers defines democracy not as how power is distributed, but as how people are regarded.

Q2. Why does this spirit come out at Christmas time?

At Christmas, ordinary social pressures are temporarily relaxed, allowing people to act on instincts they usually suppress. The season invites reflection, memory, and generosity, reminding people of shared humanity rather than social differences. Traditions, stories, and rituals—especially those centered on goodwill and gift-giving—legitimize kindness across boundaries that normally divide people. Christmas also appeals to conscience rather than competition; it encourages giving without calculation and regard without merit. In this atmosphere, people feel permitted—even expected—to practice sympathy and generosity, and the democratic spirit emerges naturally because it is emotionally and morally supported by the season itself.

Q3. Why is this spirit so hard to sustain the rest of the year?

The democratic spirit is difficult to sustain because everyday life rewards competition, efficiency, and self-interest rather than patience, humility, and generosity. Social hierarchies quickly reassert themselves, and people fall back into habits of comparison and judgment. Without deliberate effort, sympathy becomes selective and respect conditional. Economic pressures, ambition, and social routines encourage people to categorize others rather than engage them personally. Unlike Christmas, ordinary life offers little cultural reinforcement for uncalculated kindness. As a result, the spirit of democracy fades not because it is false, but because it requires moral discipline and sustained attention—qualities that are easily crowded out by the demands and distractions of daily living.

Q4. What is recommended so the spirit can be sustained year-round?

Crothers implies that sustaining the democratic spirit requires intentional moral practice rather than seasonal emotion. People must consciously carry the attitudes awakened at Christmas into ordinary life, treating others with consistent respect and goodwill. This means resisting the impulse to rank, dismiss, or ignore people based on status or convenience. Democracy endures only when individuals cultivate sympathy, humility, and generosity as habits, not exceptions. Crothers suggests that literature, reflection, and moral imagination—such as the stories that shape our sense of shared humanity—can help keep this spirit alive. Ultimately, sustaining democracy depends on daily choices to live out its moral meaning, even when no season or celebration prompts us to do so.

Key Illustrations

1. Scrooge by the Fire: Christmas as Moral Awakening

Crothers begins with a literary reflection that immediately signals his theme:

“ ‘Times have changed,’ said old Scrooge, as he sat by my fireside on Christmas Eve. ‘Up to that time I had been what the world calls a successful man, and what my conscience knew to be a hard one. I was a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner. But I did not know it. Then the Christmas Spirit took possession of me, and—presto!—change!’”

Why this matters:

Crothers uses Scrooge not as a fairy-tale conversion but as an example of how Christmas reveals moral truth about how one lives among others. Christmas exposes what success without sympathy looks like.

2. Why Christmas Generosity Feels Natural

Crothers reflects on why Christmas giving feels different from ordinary charity:

“At Christmas-time it seems natural and easy to be generous. We do not argue about it; we do not demand a careful analysis of results. We give because it is Christmas, and because it is human to give. The act seems justified by the occasion itself.”

Why this matters:

This passage shows that Christmas temporarily suspends calculation and suspicion, allowing people to act on moral instincts that democracy requires year-round.

3. The Spirit of Democracy as a Disturber of Comfort

Crothers refuses to sentimentalize democracy:

“The Spirit of Democracy is a bold iconoclast. He goes about smashing idols. He is not impressed by position, nor overawed by success. He rebukes even the captains of industry, and insists upon asking whether the lives of men and women are being lifted or merely used.”

Why this matters:

Democracy, for Crothers, is not polite benevolence. It questions systems and habits that preserve comfort for some at the cost of dignity for others.

4. Modern Help Without Humiliation

Here Crothers describes a newer approach to helping the poor:

“These modern experts go about mending broken fortunes in very much the same way in which surgeons mend broken bones. The patient is treated with skill and respect. He is not made to feel that he is under an oppressive weight of obligation, nor is he expected to express excessive gratitude.”

Why this matters:

This is one of Crothers’ clearest statements that true democratic help avoids condescension. Aid should restore strength, not create shame.

5. Democracy as Ordinary Neighborliness

Crothers pushes against heroic or dramatic visions of social reform:

“They think that one of the inalienable rights of man is the right to make his own mistakes and to learn from them. They do not wish to play Providence. They are not benefactors dispensing favors from above; they are only neighbors.”

Why this matters:

Democracy, in its moral sense, is not savior-driven. It is shared life among equals, marked by patience, restraint, and respect.

6. Helping the Needy and Raising Their Standing

This passage addresses exactly the point you raised:

“The danger of indiscriminate charity is not that it gives too much, but that it gives in the wrong way. The real aim is not merely to relieve distress, but to remove the conditions which make men dependent. The democratic spirit does not rest satisfied until it has helped a man to stand on his own feet.”

Why this matters:

Crothers is clear: relief alone is not enough. True democratic generosity seeks restoration—social, moral, and economic—so that the recipient is no longer below the giver.